Masquerade and Mimicry

Let us discuss the important developments and experiences that occupy the minds of young people nearing the end of the first third of their lives; such as the large matter of a beard, or the small matter of a philosophy of life.

Nietzsche in a letter to Paul Deussen, June 2, 18681BVN-1868,573

Exuberantly styled facial hair saw another of its cyclic revivals in past decade, with entire books, magazines and websites dedicated to such varied beard styles as the “Franz Joseph”, the “Garibaldi” and the mustache “à la Souvarov”. The barista at the coffee bar where I first typed these notes sported a dapper, pointy-ended handlebar that could rival that of the archduke Franz Ferdinand. Yes, reader: early twenty-first century hipness took about a month of stubbly, scratchy patience.

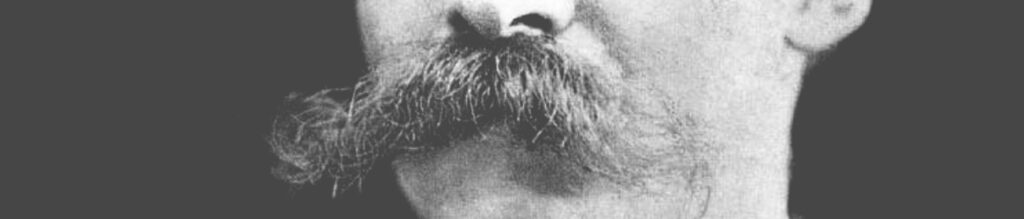

Less accessible to us, however, is the specific cultural significance each of these various styles used to carry before they were ironically subverted and re-appropriated. Take Friedrich Nietzsche’s iconic mustache—which, especially in the form it developed in his later years, would today most likely be dubbed the “walrus” or, well, the “Nietzsche”: as outrageous as it looks to us now, it’s hard to figure out exactly how it was perceived in his own day, long before Movember, and how common or uncommon it was at the time. But we can try.

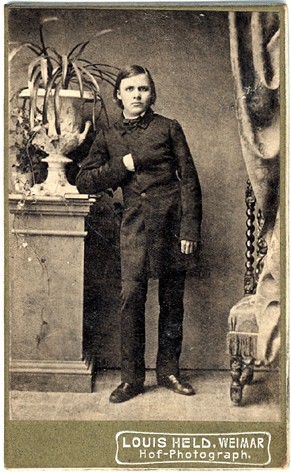

Although it varies greatly in size and grooming through the years, the mustache with clean-shaven chin and cheeks is present in every extant picture of the adult Nietzsche. As soon as hormones allowed, he went with this particular style and seemingly never looked back. Only a few photographs remain from before that time, including a precociously Napoleonic portrait taken at age sixteen (1861, on the day of his confirmation), and one in his final year before university: his last with no sign of facial hair.

Young Nietzsche must have started growing it shortly after that time, as one of his classmates reports that “[h]is mustache, which later became so extraordinarily prominent, already began to appear in school.”2Raimund Granier, a school friend of Nietzsche’s at Schulpforta. In Sander L. Gilman (ed.): Conversations with Nietzsche. A Life in the Words of his Contemporaries (translated by D.J. Parent), Oxford University Press, New York / Oxford (1987), p. 9.

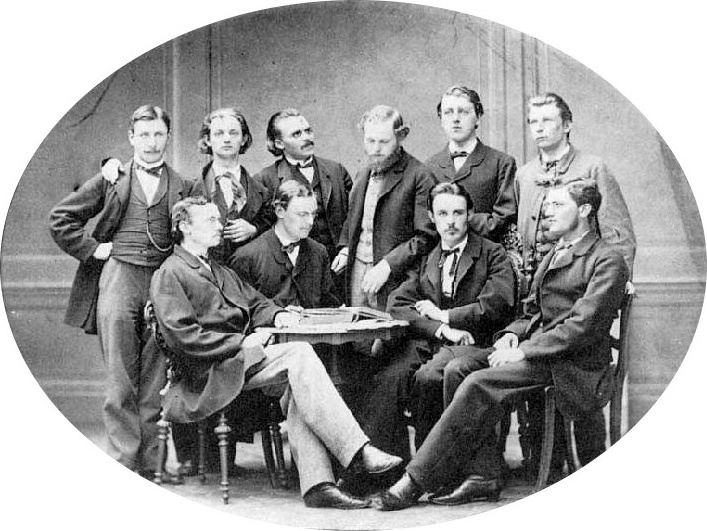

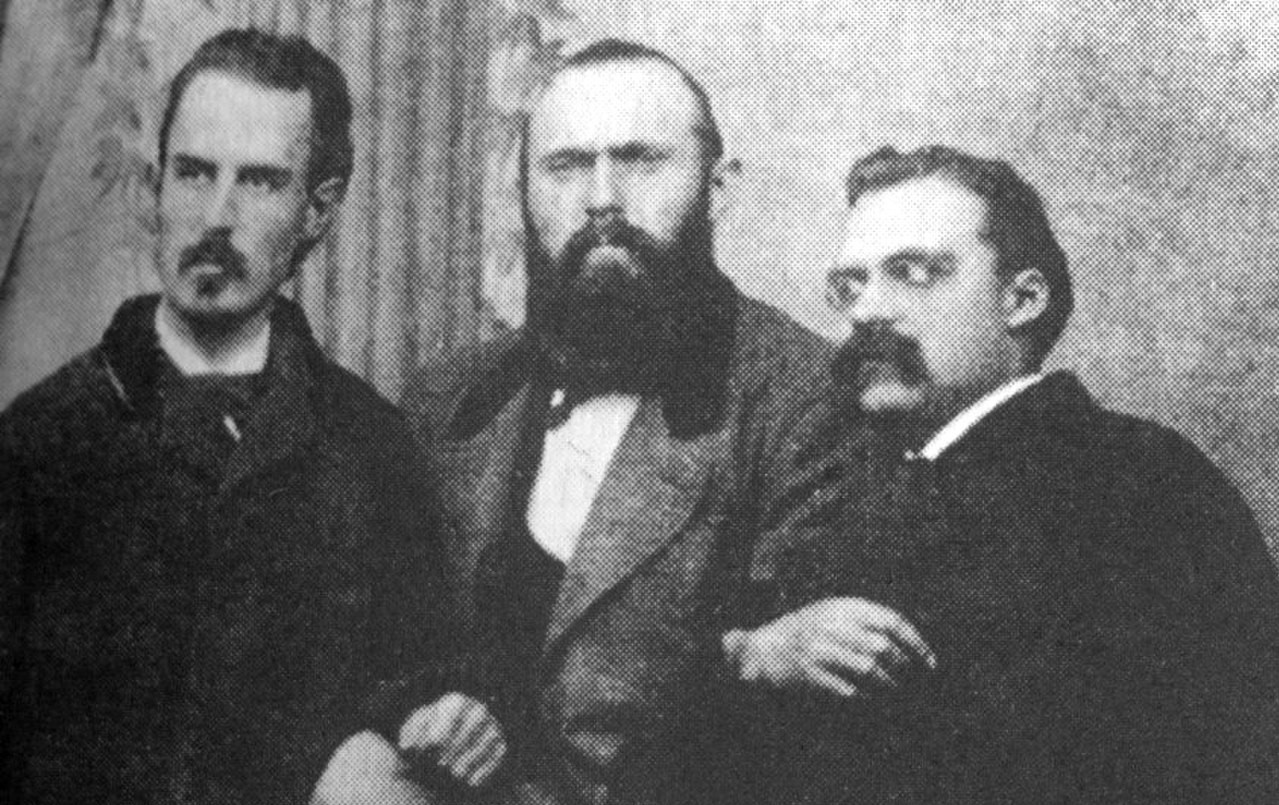

Moving to Bonn to study theology, Nietzsche was certainly not the only one there rocking the whiskers-only look. A group photograph of his student fraternity, strewn around a beer keg in cocky, studied nonchalance, shows several of his peers with respectable mustaches.

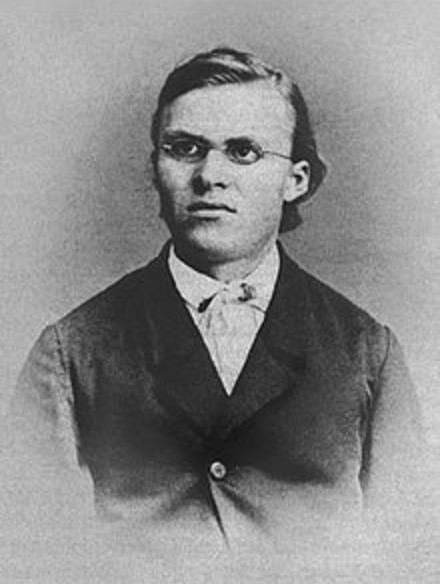

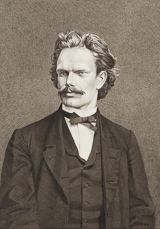

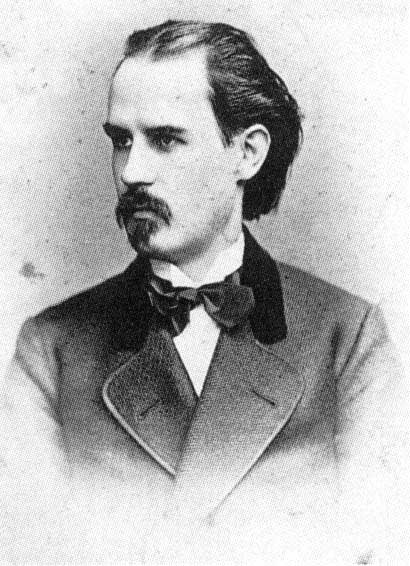

In comparison, Nietzsche, sitting directly behind the keg facing left with his right hand at his brow in a world-weary—or migrainous—gesture, looks rather inconspicuous. An individual photograph of the same period confirms as much: the future schnauzer was still a pup.

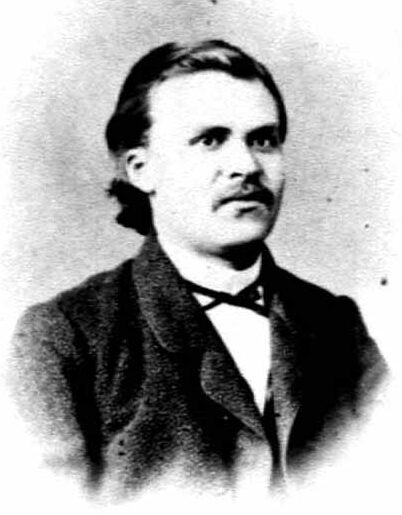

But not for long: two years later, at the University of Leipzig in 1866 (Nietzsche had switched majors from theology to classical philology by then), a fellow student noted that “[h]is appearance even then was already dominated by a stern expression and a large mustache.”3Gilman: Conversations with Nietzsche, p. 29.

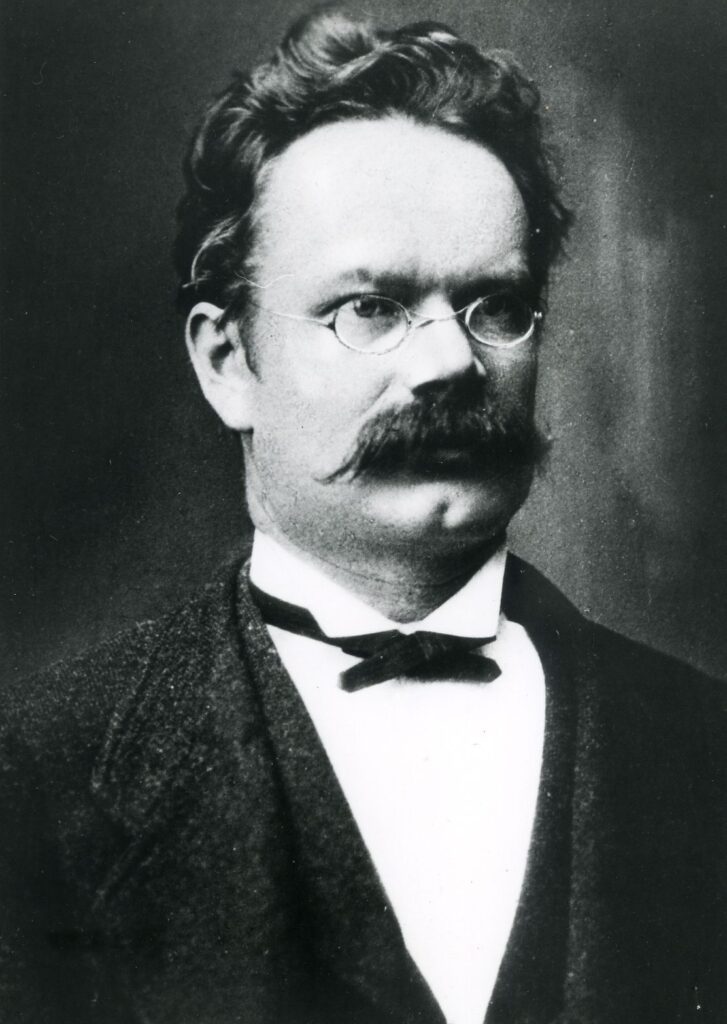

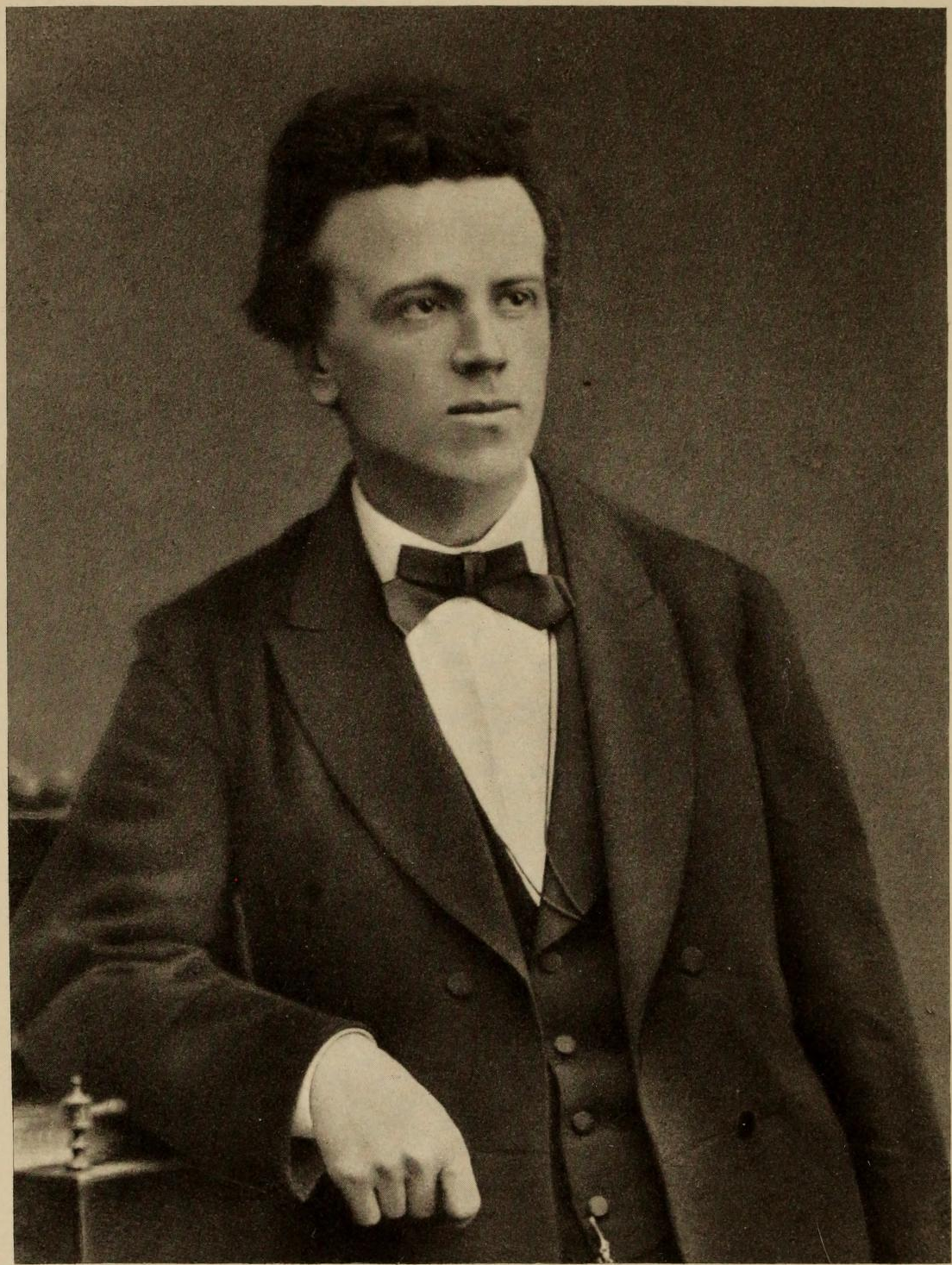

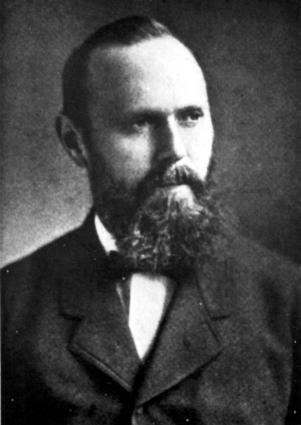

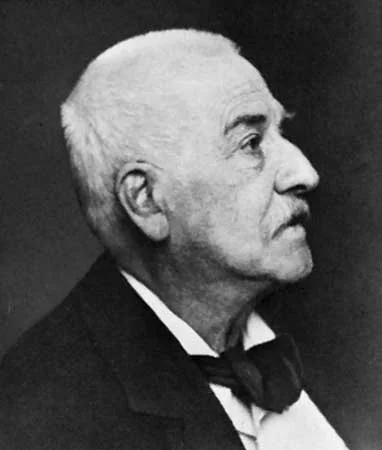

In 1867, Nietzsche attended a meeting of philologists in Halle, where he wrote to a friend: “Mustaches are all the rage here.”4BVN-1867,552 One of the people he met at the conference was the philologist and historian Curt Wachsmuth, who sported a majestic “walrus” (and in fact—as seen below in the later photograph—would come to bear a remarkable resemblance to the later Nietzsche). Friedrich’s description of this man, seven years his senior, is telling, because—considering the preoccupation with mustaches evident throughout the letter—it can be read as a direct comment on Wachsmuth’s facial hairstyle: “He really has a touch of the artist,” Nietzsche writes, “above all a powerful, bandit-like ugliness, which he carries with panache and pride.”5BVN-1867,552

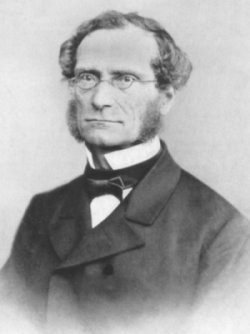

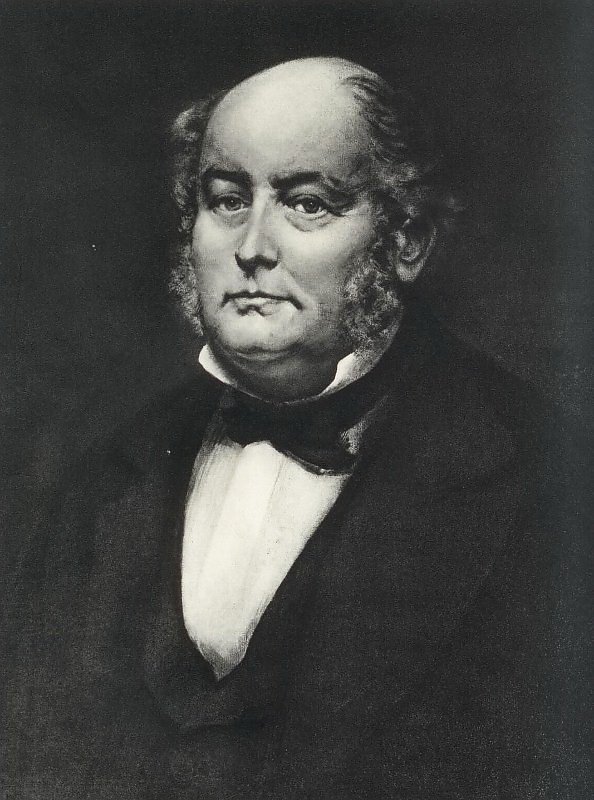

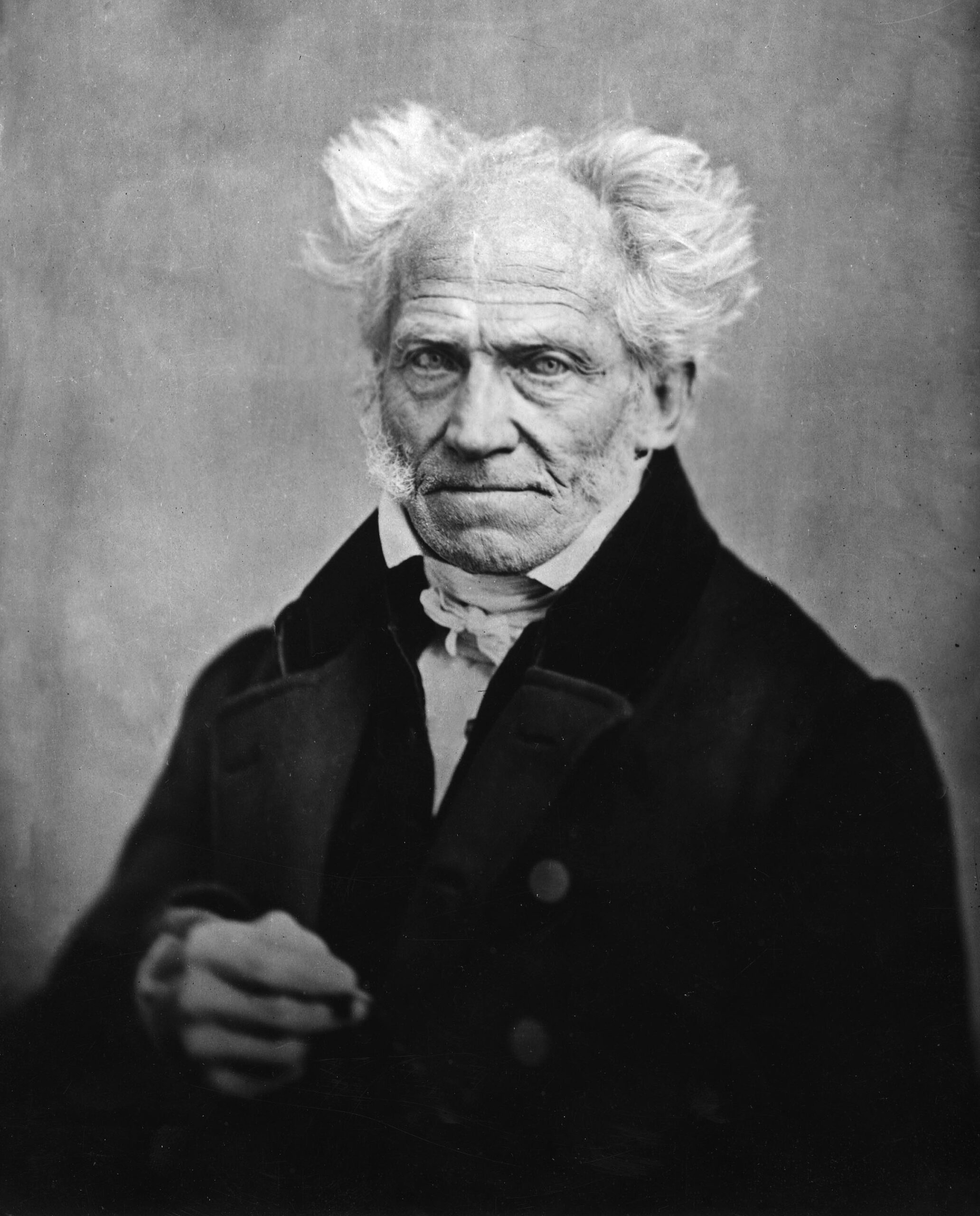

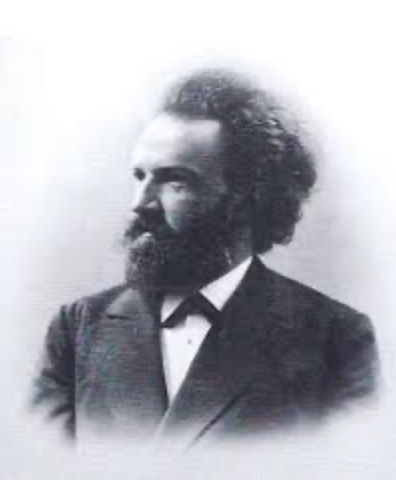

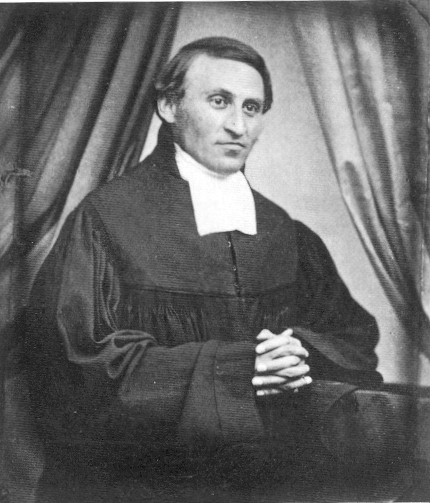

“Bandit-like ugliness” may not sound like much of an endorsement, but it must have been what Nietzsche was after: by the time he made his entrance as a young lecturer at Basel University, his own Schnurrbart had grown to considerable size. Mustaches may have been all the rage in Halle, but in Basel, this feature set him apart from the rest of the staff. Of his colleagues there, classicist Wilhelm Vischer-Bilfinger and ethnologist Johann Jakob Bachofen both wore sideburns not unlike Arthur Schopenhauer’s; Franz Overbeck, who was to become one of Nietzsche’s closest friends, was beardless. His pupil and later friend Heinrich Köselitz developed a full beard through the years, as did Nietzsche’s old schoolmates Carl von Gersdorff and Paul Deussen. Another lifelong friend, fellow Leipzig student Erwin Rohde, wore a Zappa-esque mustache-and-soul-patch combo. Nietzsche’s father Carl Ludwig appears clean-shaven in rare extant pictures. Among his older acquaintances that could be deemed surrogate father figures, Nietzsche’s philology professor Friedrich Ritschl had neatly trimmed sideburns; composer Richard Wagner’s distinctive neckbeard is well known. Only his Basel colleague Jacob Burckhardt, whom he admired, had a mustache without beard, albeit a lighter-colored and much less conspicuous one than Nietzsche’s. And finally, Zarathustra, Nietzsche’s “son”—as he often called his creation6BVN-1883,407; BVN-1883,421; BVN-1883,431; BVN-1883,438; BVN-1884,514; BVN-1884,516; NF-1884,26[394]; BVN-1884,518; BVN-1884,528; BVN-1885,600; NF-1886,6[4]; BVN-1886,740—has a suitably prophetic beard and is described several times as thoughtfully “stroking” it.7Za-II-Wahrsager; Za-IV-Nothschrei; Za-IV-Zeichen

Though not exactly unique, Nietzsche’s whiskers were uncommon enough in intellectual circles to become something of a trademark, a fact of which he was not unaware. “Meet me at the station,” he wrote to his future friend Resa von Schirnhofer in 1884, “you will recognize me by my large mustache.”8BVN-1884,500 It was clearly one of the first things people noticed about him. What message, then, did it communicate about its wearer?

Trim as a Tin Soldier

Overall, those who met Nietzsche in person were surprisingly unanimous in their first impressions. Many mentioned the mustache, and at least four independent witnesses, over the course of a decade, came up with the exact same association:

He […] had a thoroughly military appearance and could have been taken for an officer in civilian clothes […] his mouth shaded by a huge blond mustache.

Paul Heinrich Widemann, 18759Gilman: Conversations with Nietzsche, p. 61.

The thickly drooping mustache as well as the sharp facial features seemed to lend him the appearance of a cavalry officer.

Edouard Schuré, 187610In Raymond Benders and Stephan Oettermann (eds.): Friedrich Nietzsche. Chronik in Bildern und Texten, dtv, München, 2000, p. 370; translation from Julian Young: Friedrich Nietzsche. A Philosophical Biography, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge,2010, p. 223.

A commanding personality with a rather unusual appearance, whom one would therefore well remember: a large bushy mustache gave the face a martial air, a striking profile; involuntarily one would have thought, a Prussian officer in civilian clothes.

Sebastian Hausmann, mid-1880s11Gilman: Conversations with Nietzsche, p. 133.

The thick Vercingetorix mustache […] allowed him so little to resemble the type of a German scholar that he called to mind rather […] an Italian or Spanish higher officer in civilian clothes.

Adolf Ruthardt, 188512Gilman: Conversations with Nietzsche, p. 183.

These descriptions suggests that at least one cultural convention (or cliché) hasn’t changed: that of the “martial mustache”,13Gilman: Conversations with Nietzsche, p. 246. which today lives on in a particularly iconic form.

I am of course referring to the cop ’stache.

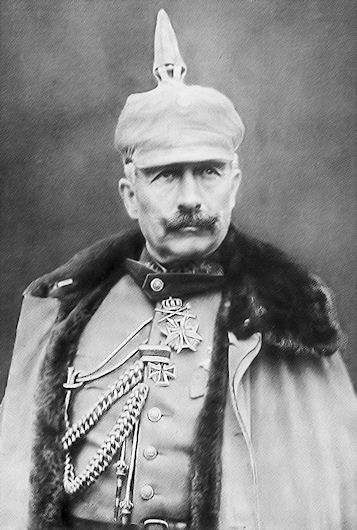

The martial mustache suggests an old-fashioned, dapper, hands-on masculinity: a pragmatic savoir-faire combined with, perhaps, a somewhat hot-headed preparedness to action. The fact that Nietzsche shared this look with Prussian statesmen Otto von Bismarck and Kaiser Wilhelm II confirms the militaristic connotations it carried. Though a civil servant with no military career to speak of, Chancellor Bismarck was notorious for wearing a uniform in public; Wilhelm II was positively obsessed with them and had one made for every possible occasion.

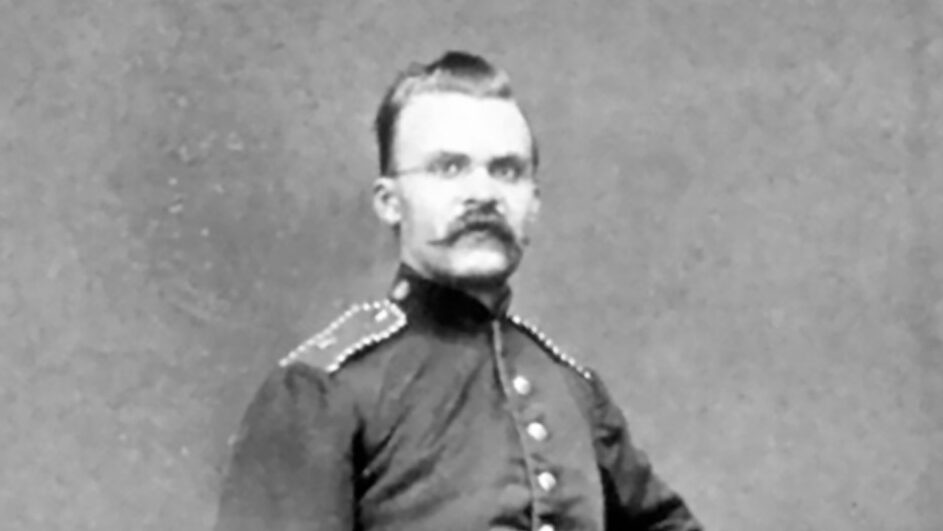

Indeed, Nietzsche himself spent the year between his student days and his appointment in Basel—the period when his mustache truly took off—in uniform. He signed up for voluntary military service, a life-defining episode in the coming of age of many a 19th-century German youth. A photograph from this time shows the young Freiwilliger in full military regalia, saber drawn, chin raised, a phenomenally decorated Pickelhaube (spiked helmet) by his side, and a defiant gaze he later described to his friend Rohde as “such a sour, bitterly angry face”—he was “about to pounce on his bungling photographer,” Nietzsche jokingly explained, when the man ducked behind the hood of his camera and yelled: “Now!”.14Letter to Erwin Rohde, 6 Aug. 1868. BVN-1868,583

What the black-and-white picture does not do justice is that the uniform of a mounted artillery officer would have been a dashing Prussian blue (dunkelblau, before the introduction of the more utilitarian feldgrauer Waffenrock in the early 20th century), with bright red piping around the “Swedish cuffs” (horizontal turned-back panels with two buttons side by side) and down the front edge. The shoulder straps appear to be edged with a twisted black and white cord, the identifying mark of one-year volunteers like Nietzsche. Visible on the side of his collar is the so-called Gefreitenknopf, a silver or brass button adorned with the Prussian eagle designating the rank of Gefreiter (lance corporal), which had been awarded to him a few months earlier; there would have been one on either side. The tassel dangling from the sable’s hilt is a portepee or sword knot, also a mark of military rank.

Missing from the picture are a white belt and shoulder strap, possibly due to a severe chest wound Nietzsche sustained during a horse-riding drill, which kept him out of action for a large part of his voluntary service (more on this soon-ish, in another chapter); although the creases in his tunic running from his left shoulder to his right side and across his waist indicate where he would have usually worn them. Even without this finishing touch, the portrait, trim as a little tin soldier, shows the mustache in its proper cultural context and illustrates the impression the 24-year old must have made—even in civilian clothes.

A slightly different, but related reading of Nietzsche’s appearance was offered by a young lady who met him in Sils-Maria: she described him as a “strong, well-dressed figure with the full, rosy face and the mustache [of] a Junker rather than a scholar or an artist.”15Marie von Bradke, 1886, in Gilman: Conversations with Nietzsche, p. 190. The Prussian Junker class was an old lineage of landed nobility whose members played a dominant role in many areas of society. The comparison suggests, then, that Nietzsche’s mustache lent him a certain “aristocratic” aura. One of his university students indeed mentioned “a striking nobility of appearance”;16Leonhard Adelt, 1870, in Gilman: Conversations with Nietzsche, p. 39. another pupil described him as “the elegant and distinguished looking man with the large mustache”;17Kurt von Miaskowski, in Gilman: Conversations with Nietzsche, p. 53. to a later acquaintance, the mustache “called to mind […] a Southern French nobleman”.18Adolf Ruthardt, 1885, in Gilman: Conversations with Nietzsche, p. 183. This effect would have pleased Nietzsche, as he often speculated about being of noble ancestry himself, claiming that he descended from a Polish aristocratic family by the name of Niëtzki or Niëzki:19NF-1882,21[2], BVN-1888,1014

Indeed, he told me with obvious pleasure how he was frequently addressed by Poles as their countryman and that according to a family tradition the Polish descent of the Nietzsches from a Niezki was certain. This was news to me at the time and interested me, since I had in a historical painting of Jan Matjeko’s [sic] in Vienna seen typically shaped heads with a far greater similarity than the merely superficial one of the mustache, and he seemed delighted to hear this. For he was very proud of his Polish background.

Resa von Schirnhofer, 188420Gilman: Conversations with Nietzsche, p. 148.

The painting in question was Jan Matejko’s John III Sobieski at Vienna, which depicts King John III Sobieski of Poland after defeating the Turks in the Battle of Vienna in 1683. It was on display there in 1883 (the year before Resa von Schirnhofer met Nietzsche in Nice) to commemorate the 200th anniversary of the victory,21P.M. Dabrowski: Commemorations and the Shaping of Modern Poland, Indiana University Press, Bloomington & Indianapolis (2004), p. 59. and indeed features several mustachioed gentlemen, including the King himself.

In fact, it appears that this element alone already suggested Eastern-European nobility: “The bushy mustache,” an anonymous visitor wrote shortly after Nietzsche’s death, “gave his head a somewhat gallant effect and markedly stressed the Slavic type.”22Anonymous description of the recently deceased Nietzsche, in Gilman: Conversations with Nietzsche, p. 261.

Although these aristocratic connotations seem to lend the mustache a gentler and more genteel cultural meaning, they, too, ultimately pertained to the military sphere. It was the same old-time masculinity and discipline, the same authority and elegance, only sublimated into the chivalrous. This was especially true in Prussia, where both spheres were closely intertwined. Many members of the Junker class occupied high military positions; the army’s old-fashioned, colorful uniforms, sabers, and decorations, as well as the preoccupation with horse-riding, played into the remembered splendor of a feudal era that was being reluctantly given up to the past. Uniform-loving Chancellor Bismarck was a Junker himself, and Kaiser Wilhelm II, of the Hohenzollern dynasty, epitomized the re-appropriation of the uniform as court dress.

Cultivated Contrasts

We now have a general idea of what Nietzsche’s mustache signaled to his contemporaries: the pride and panache of a bandit; the irascible temper of a military man; and the aristocratic arrogance of Prussian nobility.

These implied character traits present quite a contrast to the mild-mannered armchair intellectual one might expect in a classical philology department in a sleepy Swiss university town. And indeed, new students at Basel University, where Nietzsche lectured as a professor for ten years, were “struck by his appearance. A military type! Not a ‘scholar’!”23Gilman: Conversations with Nietzsche, p. 57. He looked nothing like the artistically inspired thinker they had pictured behind his early writings and lectures (which were by then known, at least by reputation, in student circles). “I had imagined a kind of Schiller head,”24“Ich hatte mir so eine Art Schillerkopf vorgestellt.” Paul Widemann, 1875, in Sander L. Gilman and Ingeborg Reichenbach (eds.): Begegnungen mit Nietzsche, p. 250. writes one student, referring to the shoulder-length curls and sensitive features of the 18th-century romantic poet; “the long hanging mustache,” writes another, “deprived the face of that intellectual expression which often gives even short men an impressive air.”25Student Ludwig von Scheffler, 1876, in Gilman: Conversations with Nietzsche, p. 65. Emphasis mine.

But then, when Professor Nietzsche spoke, his students were in for a second surprise: “such modesty, indeed humility, of deportment”!26Student Ludwig von Scheffler, in Gilman: Conversations with Nietzsche, p. 64. His mild voice and attentive body language subverted both their original expectations and their initial impressions of his appearance. No, this “Offizier in Civil” did not bark orders; he was not aloof or arrogant but “very accessible for visits”;27Student Jakob Wackernagel, in Gilman: Conversations with Nietzsche, p. 36. far from being hot-tempered, he had a way of suffering students’ gaffes or lack of preparation in class with a protracted, ironic, but not altogether unbenign silence.28High school pupil Moritz, Student Leonhard Adelt, in Gilman: Conversations with Nietzsche, pp. 37–39. He was, in the words of a colleague, “most touchingly kind-hearted and sensitive”.29Julius Piccard, ca. 1870, in Gilman: Conversations with Nietzsche, p. 34.

Here was a man whose inner nature, outward appearance, and public persona as an author were very much at odds.

Was this dissonance merely the mark of a socially maladroit professor who, unaware of fashion or dress codes, throws together an arbitrary outfit and stumbles into a comically incongruous trademark style? No. Although he was no dandy (and, with his low income, was forced to wear his clothes down to the threads), Nietzsche certainly did not share his colleague Burckhardt’s ascetic contempt for sartorial matters; his “whole personality showed anything but indifference to personal appearance.”30Student Ludwig von Scheffler, in Gilman: Conversations with Nietzsche, p. 64. Nietzsche’s letters home contained fairly detailed orders for the family tailor in his hometown Naumburg,31BVN-1862,298, BVN-1869,2, BVN-1869,29, BVN-1870,67, BVN-1872,208, BVN-1873,308, BVN-1874,358, BVN-1875,440, BVN-1875,442 as well as joyful reports whenever he found a local tailor up to his standards.32BVN-1888,1033, BVN-1888,1122, BVN-1888,1137, BVN-1888,1143, BVN-1888,1175 It seems likely, then, that he was well aware that he did not look the way he was expected to, and that this was by choice. Even the uniformed photograph from his year in military service was a kind of deliberate façade: it was taken “in mock”, writes Nietzsche’s sister, as a kind of fancy dress, and later led to much merriment and many “misunderstandings”.33Elisabeth Förster-Nietzsche, in Gilman and Reichenbach: Begegnungen mit Nietzsche, p. 72.

Nietzsche not only consciously cultivated the contrast between his appearance and character, he even seemed to playfully exploit it, reveling in its effect. In 1867, still a student, Nietzsche took horse-riding exercises with his friend Erwin Rohde; afterwards, they often went straight from the stables to university, where they attended Professor Ritschl’s philology classes in full gear, riding crop included. As not many classicists engaged in this kind of “rugged” activity, these two “young gods” were met with admiring stares from their peers34Gilman and Reichenbach: Begegnungen mit Nietzsche, pp. 68–69.—for a contemporary equivalent, think of a couple of grad students casually strolling into a seminar in full leather motorcycle outfits and helmets!

The effect would not have been nearly as strong if Nietzsche and Rohde had been a pair of ordinary, non-academic cadets, from whom such activities are to be expected, rather than two of the most gifted and promising intellectuals of their generation. Military types were a dime a dozen in Prussian society, as were mild-mannered students, but it was the unexpected combination of the two that made their appearances so impressive. And, conversely, the same contrast likely enhanced the impact of their brilliant contributions to the class.

Masquerade and Mimicry

There are several reasons why a young, exceptionally talented student might choose to appear as his polar opposite. It might be a subconscious attempt to lower intellectual expectations, and thus to be guaranteed an admiring audience through the element of surprise. It might stem from a reluctance to embody the boringly predictable image of the diligent, bookish student; a desire not to be too easily pigeonholed, to incorporate a certain incongruity, a sense of mystery, an “edge”. Perhaps it signals to fellow intellectuals: “I do not belong exclusively to you; do not imagine that I will think, speak, or act the way you expect me to.”

Or—it might simply be a disguise. One commentator, noting Nietzsche’s “obsession with military appearances”, suggests that “he deliberately wanted to mislead the world with that mustache of his.”35L. Chamberlain: Nietzsche in Turin: An Intimate Biography, Picador, New York (1996), p. 37. Emphasis mine. That is: rather than wanting to appear more sophisticated or “interesting” by explicitly contrasting his intellect with a different sphere of excellence—military discipline—, perhaps Nietzsche found it convenient at times to present himself as less interesting than he really was; to disappear entirely behind this façade, to appear as no more than what the mustache signaled to the world.

This kind of masquerade is precisely the subject of Nietzsche’s only comment on the Schnurrbart matter in his philosophical writings:

Thus the gentlest and most reasonable of men can, if he wears a large mustache, sit as it were in its shade and feel safe there—he will usually be seen as no more than the appurtenance of a large mustache, that is to say a military type, easily angered and occasionally violent—and as such he will be treated.36“So kann der sanftmüthigste und billigste Mensch, wenn er nur einen grossen Schnurrbart hat, gleichsam im Schatten desselben sitzen, und ruhig sitzen,—die gewöhnlichen Augen sehen in ihm den Zubehör zu einem grossen Schnurrbart, will sagen: einen militärischen, leicht aufbrausenden, unter Umständen gewaltsamen Charakter—und benehmen sich darnach vor ihm.” M-381

It can be a mistake to confuse the author with the individual, but in this case it is impossible to ignore the walrus in the room: coming from Nietzsche, how could this little observation not be at least partly autobiographical? Confirming the military connotations of the mustache, he presents it as a strategic camouflage, a kind of mimicry, used by a sensitive soul to avoid being recognized for what he is, in the way that a harmless, defenseless animal might imitate the brightly colored cautionary markings of a poisonous species.

But mimicry can also work the other way around. Some predators imitate a harmless species to avoid alarming their prey. Perhaps this militaristic exterior is in fact relatively harmless compared to what it hides. Perhaps being pigeonholed is exactly the decoy Nietzsche needed: an “easily angered and occasionally violent”, but intellectually harmless caricature that was readily put aside as predictable and familiar (Junkers and military officers lined the streets of Prussia, if not its philology departments), prompting the world to look no further, to suspect no hidden depths below the surface.

And just like that, we have stumbled upon something of a theme in Nietzsche’s philosophy.

Hidden Depths

“Everything profound loves masks,” Nietzsche writes in Beyond Good and Evil, and “the most profound things go so far as to hate images and likenesses.” In the same way that a truly wise, diligent student does not necessarily appear wise and diligent, and may even have an instinctive aversion to such outward congruence, might not true depth be averse to the desire to appear profound? “Wouldn’t just the opposite be a proper disguise for the shame of a god?”37“Alles, was tief ist, liebt die Maske; die allertiefsten Dinge haben sogar einen Hass auf Bild und Gleichniss. Sollte nicht erst der Gegensatz die rechte Verkleidung sein, in der die Scham eines Gottes einhergienge?” JGB-40

So step aside instead! Run away and hide! And be sure to have your masks and your finesse so people will mistake you for something else, or be a bit scared of you!38“Geht lieber bei Seite! Flieht in’s Verborgene! Und habt eure Maske und Feinheit, dass man euch verwechsele! Oder ein Wenig fürchte!” JGB-25

The German “Feinheit”, translated here as “finesse”, is more than mere “refinement”. Often pluralized, it suggests the playful art of innuendo or insinuation, of “subtleties”, as in: “The best man’s speech was peppered with subtleties.” In that sense, even coarseness, adopted as a cunning disguise, can be a form of “finesse”, a subtle sleight-of-hand:

There are events that are so delicate that it is best to cover them up with some coarseness and make them unrecognizable.39“Es giebt Vorgänge so zarter Art, dass man gut thut, sie durch eine Grobheit zu verschütten und unkenntlich zu machen […].” JGB-40

Nietzsche’s writing combines both types of mimicry: that of the prey, by shrouding delicacy in coarseness, and that of the predator, by disguising what Nietzsche predicted would be world-shattering ideas in seemingly harmless, easily pigeonholed superficiality. His thought may be subtle, complex and demanding, but his prose is among the most readable in German philosophy. His sentences are short and interspersed with engaging question marks and exclamation points. It does not appear profound or difficult or serious in the way that Immanuel Kant’s page-long sentences do, where even figuring out what is going on grammatically requires an advanced degree in German linguistics and a lot of patience, before even attempting to understand the underlying argument.

To coin a phrase: Nietzsche’s philosophy wore a mustache. His prose employed the same disguises as its author: a bandit-like pride and panache; a deceptive simplicity, easily brushed aside as no more than it appears to be; brisk aphorisms, the roar of cannons, the thunder of military jargon; the Gallic gallantry of Human, All Too Human’s maxims. And there is meaning in that deliberate confusion itself: it belies a black-and-white world where things are exactly as they seem; where the just, the wise, the generous and the tender are readily distinguishable from the selfish, the malignant and the brutal; where the former wear white hats and the latter dress in black.

Nietzsche’s literary disguises may have succeeded to the extent that to this day, those not intimately familiar with his work and life take his outward image of militaristic bravado at face value, and it still comes as a surprise to new readers that in the shadow of that fierce mustache lurks a “gentle and reasonable man”40 See footnote 36, M-381 and a nuanced thinker. No wonder his philosophy comes with a warning label for those wanting to understand it: “Do not mistake me for something else!”41 “Verwechselt mich vor Allem nicht!” EH-Vorwort-1

Notes

- 1

- 2Raimund Granier, a school friend of Nietzsche’s at Schulpforta. In Sander L. Gilman (ed.): Conversations with Nietzsche. A Life in the Words of his Contemporaries (translated by D.J. Parent), Oxford University Press, New York / Oxford (1987), p. 9.

- 3Gilman: Conversations with Nietzsche, p. 29.

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9Gilman: Conversations with Nietzsche, p. 61.

- 10In Raymond Benders and Stephan Oettermann (eds.): Friedrich Nietzsche. Chronik in Bildern und Texten, dtv, München, 2000, p. 370; translation from Julian Young: Friedrich Nietzsche. A Philosophical Biography, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge,2010, p. 223.

- 11Gilman: Conversations with Nietzsche, p. 133.

- 12Gilman: Conversations with Nietzsche, p. 183.

- 13Gilman: Conversations with Nietzsche, p. 246.

- 14Letter to Erwin Rohde, 6 Aug. 1868. BVN-1868,583

- 15Marie von Bradke, 1886, in Gilman: Conversations with Nietzsche, p. 190.

- 16Leonhard Adelt, 1870, in Gilman: Conversations with Nietzsche, p. 39.

- 17Kurt von Miaskowski, in Gilman: Conversations with Nietzsche, p. 53.

- 18Adolf Ruthardt, 1885, in Gilman: Conversations with Nietzsche, p. 183.

- 19

- 20Gilman: Conversations with Nietzsche, p. 148.

- 21P.M. Dabrowski: Commemorations and the Shaping of Modern Poland, Indiana University Press, Bloomington & Indianapolis (2004), p. 59.

- 22Anonymous description of the recently deceased Nietzsche, in Gilman: Conversations with Nietzsche, p. 261.

- 23Gilman: Conversations with Nietzsche, p. 57.

- 24“Ich hatte mir so eine Art Schillerkopf vorgestellt.” Paul Widemann, 1875, in Sander L. Gilman and Ingeborg Reichenbach (eds.): Begegnungen mit Nietzsche, p. 250.

- 25Student Ludwig von Scheffler, 1876, in Gilman: Conversations with Nietzsche, p. 65. Emphasis mine.

- 26Student Ludwig von Scheffler, in Gilman: Conversations with Nietzsche, p. 64.

- 27Student Jakob Wackernagel, in Gilman: Conversations with Nietzsche, p. 36.

- 28High school pupil Moritz, Student Leonhard Adelt, in Gilman: Conversations with Nietzsche, pp. 37–39.

- 29Julius Piccard, ca. 1870, in Gilman: Conversations with Nietzsche, p. 34.

- 30Student Ludwig von Scheffler, in Gilman: Conversations with Nietzsche, p. 64.

- 31

- 32

- 33Elisabeth Förster-Nietzsche, in Gilman and Reichenbach: Begegnungen mit Nietzsche, p. 72.

- 34Gilman and Reichenbach: Begegnungen mit Nietzsche, pp. 68–69.

- 35L. Chamberlain: Nietzsche in Turin: An Intimate Biography, Picador, New York (1996), p. 37. Emphasis mine.

- 36“So kann der sanftmüthigste und billigste Mensch, wenn er nur einen grossen Schnurrbart hat, gleichsam im Schatten desselben sitzen, und ruhig sitzen,—die gewöhnlichen Augen sehen in ihm den Zubehör zu einem grossen Schnurrbart, will sagen: einen militärischen, leicht aufbrausenden, unter Umständen gewaltsamen Charakter—und benehmen sich darnach vor ihm.” M-381

- 37“Alles, was tief ist, liebt die Maske; die allertiefsten Dinge haben sogar einen Hass auf Bild und Gleichniss. Sollte nicht erst der Gegensatz die rechte Verkleidung sein, in der die Scham eines Gottes einhergienge?” JGB-40

- 38“Geht lieber bei Seite! Flieht in’s Verborgene! Und habt eure Maske und Feinheit, dass man euch verwechsele! Oder ein Wenig fürchte!” JGB-25

- 39“Es giebt Vorgänge so zarter Art, dass man gut thut, sie durch eine Grobheit zu verschütten und unkenntlich zu machen […].” JGB-40

- 40See footnote 36, M-381

- 41